Strengthening Capacity of Community Health Systems for Epidemic Response

Strengthening Capacity of Community Health Systems for Epidemic Response

MSH at the 2018 Health Systems Research Symposium

Last week, at the 5th Global Symposium on Health Systems Research in Liverpool, MSH presented on the approach and lessons learned during the community-level response to the 2017 plague outbreak in Madagascar.

All infectious disease epidemics begin at the community level. Left unnoticed or unchecked, a single unusual case can quickly spread, threatening the health, livelihood, and security of an entire nation and even the world. Cholera outbreaks in Rwanda, Avian Influenza on the border of Uganda, and Ebola in West Africa have shown us how difficult it can be to detect and quickly respond to infectious outbreaks.

In Madagascar, bubonic plague is endemic. Typically, the country will record between 400 and 600 cases annually. However, in 2017, the plague also took the pneumonic form, making it highly contagious. Spreading from person to person through the air, pneumonic plague is much more virulent and contagious than bubonic plague, which spreads to humans through infected flea bites or direct physical contact with infected cadavers. Left untreated, pneumonic plague is fatal. The severity of this outbreak led the Government of Madagascar to declare a level two plague epidemic on September 30, 2017.

Both bubonic and pneumonic plague are treatable with antibiotics; therefore, timely case identification is critical for saving lives and controlling the spread of diseases. The Madagascar Ministry of Public Health, with support from the World Health Organization (WHO), mobilized all health partners in September 2017 and established a multisectoral national response coordination committee to develop a national response plan and implement a series of response and control measures.

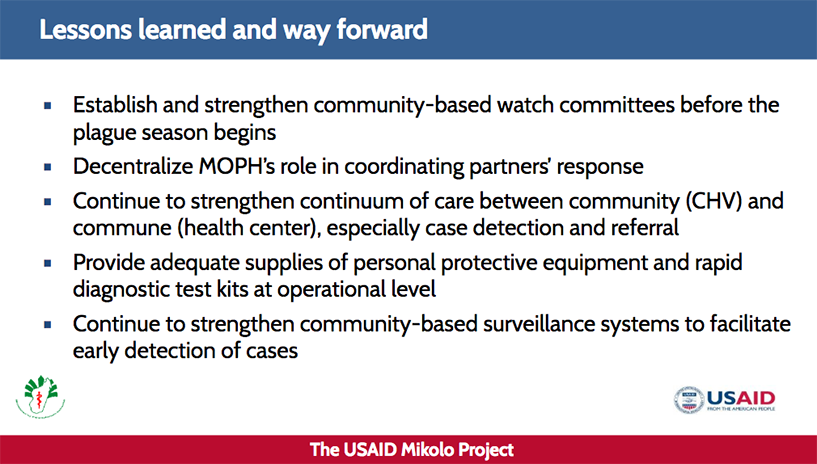

One of the largest gaps in global health security is around community preparedness. MSH works with countries and communities to help them deliver high-quality health services that meet the unique health needs of vulnerable populations, while also making sure that communities, health managers, and country leaders are able to prevent, detect, prepare for, and respond to potential outbreaks.

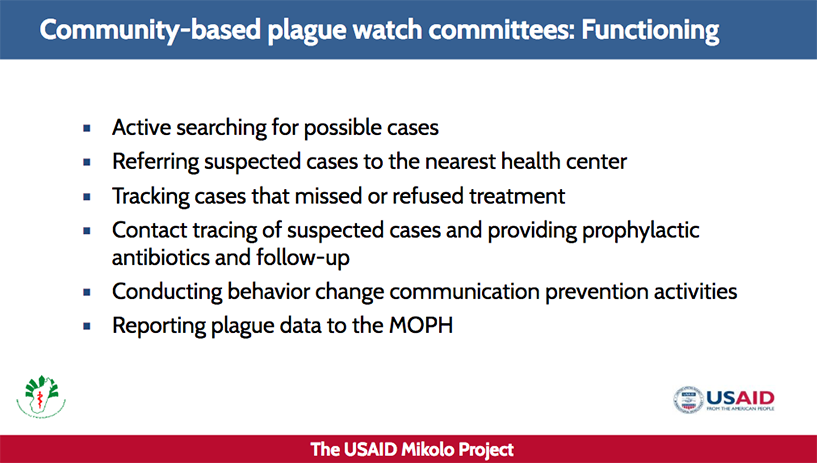

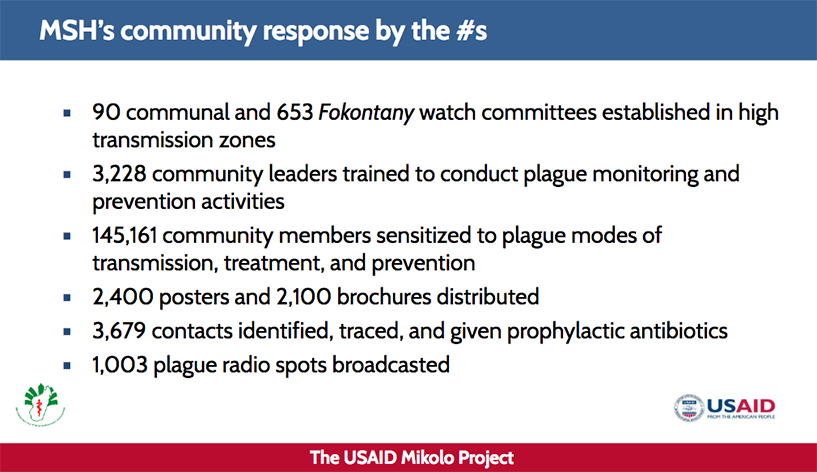

The USAID Mikolo Project, implemented by MSH, led the community-level response in 90 communes and 653 Fokontany (villages) by facilitating the creation of plague monitoring committees. These committees included community leaders, community health volunteers (CHVs), and basic health facility workers who participated in activities for case detection and referral and for prevention and surveillance.

Committee members educated the population about the plague, its symptoms, where to go for testing and treatment, and how to identify suspected cases and conduct contact tracing.

The community-level response was particularly crucial in controlling the epidemic. For example, after a man and his son died in November in the remote village of Angalampona in the Miarinarivo commune, the Village Chief, who had received training on plague prevention, suspected that the two men had died of the disease. The Village Chief immediately informed the head of the health center in Miarinarivo, which triggered an investigation by the district health authorities who, along with the Miarinarivo CVC, USAID Mikolo staff, and a team from WHO, traveled to the village with an ambulance, antibiotics, disinfecting spray equipment, and individual protective equipment.

Upon arrival, the Village Chief and a CHV brought the team to the household of the deceased. Four family members were experiencing symptoms of pneumonic plague and were immediately rushed to the health center, where two of them soon died. Two girls, aged 5 and 15 years, were stabilized upon being administered antibiotic prophylactic treatment. Serological tests at the Pasteur Institute of Madagascar confirmed that both girls had pneumonic plague. Four days later, a second investigative team of district health authorities and USAID Mikolo and WHO staff met with 32 local health and community leaders from Miarinarivo commune to review the situation and plan and coordinate a response. No further cases have been identified in this village.

As a result of the country’s rapid and collaborative response, the outbreak was officially declared over on November 27, 2017, less than two months after it began. The development and implementation of a strategy that brought the community into the plague response proved to be an effective way to strengthen the overall health system’s ability to respond rapidly to an outbreak. Working at the community level enabled response efforts to support the health needs of people the formal health system couldn’t reach.

Stopping outbreaks at the source requires comprehensive, resilient primary health care services and systems with working components: strong leadership, engaged communities, labs and hospitals, pharmaceutical systems and supply chains, and disease surveillance systems.

In Rwanda, MSH developed a unified, transparent, and sustainable electronic surveillance and response system that supports crisis response at all levels. Our work enabled near real-time tracking and reporting of disease outbreak events, and we are now also connecting human health and animal health systems to support decision making and rapid response. In collaboration with Rwanda’s Government, we are extending the system to the community level so that early warning and response can stop outbreaks at the source. Since 2015, the system has identified an average of 530 probable outbreaks per year.

In 2016, thanks to the system, Rwanda efficiently investigated 18 outbreaks nationwide. Surveillance teams investigated probable outbreaks and combined outbreaks for linked cases, rejecting others when suspected cases were not confirmed.

Related resource