Without ‘Concrete’ Directives, New UHC Agreement Could Fall Flat

Without ‘Concrete’ Directives, New UHC Agreement Could Fall Flat

By: Amy Lieberman, Jenny Lei Ravelo

This story was originally published by Devex

The onus to help everyone — including the most marginalized — secure universal health care coverage will likely depend more on individual government spending than on new foreign assistance, experts say.

Funding will be a critical, but not guaranteed, element in the forthcoming universal health coverage agreement governments will sign in September during the opening of the U.N. General Assembly session.

“Aid is not going to help achieve the global health goals. It has to come from domestic spending. But aid is very important for purposes of equity and that the poor do not get left behind.”

Jacob Hughes, senior director of health systems, Management Sciences for Health

“The idea is to challenge governments on how they can reach the goal of UHC that was elaborated in the SDGs. It is a matter of generating political will to move towards UHC. A lot of countries are doing that,” said Shannon Kowalski, director of advocacy and policy of the International Women’s Health Coalition.

“We do not think we will see real funding pledges put on the table, but what I think we will see is a discussion about the best practices and evidence for funding the systems.”

The current “zero draft” of the UHC agreement, published in May, recognizes the need for a “paradigm shift” and a boost in domestic investment to guarantee health care access for all. But it does not include specific domestic funding commitments, which will be key for full UHC implementation, global health experts tell Devex.

Peter Sands, executive director of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, hopes September’s U.N. General Assembly will be an opportunity to highlight the need to broaden the conversation around UHC, as well as financing, he told Devex.

“Financing of health care in the poorest countries in the world is simply nowhere near enough and getting the levels of fiscal mobilization to a place where UHC can be delivered is going to involve some tough leadership and choices,” Sands said.

“It inevitably involves a sustained investment in health care workforces and supply chains and private health care facilities, which take time to do and maybe do not coincide with individual leader’s political cycles. If you do not have the political leadership, you can only go so far with a technocratic approach,” Sands continued.

At least half the world’s population lack access to essential health care services — and up to one-third of the world’s population are on track to remain without access to health services by 2030, according to the draft document.

An estimated $176 billion is needed by 2030 for the 54 lowest-income countries to provide their populations with affordable and quality health services, according to World Bank estimates.

But the question is who will foot the bill.

“With all of the things that country leaders are saying they want to achieve with UHC, the funding isn’t there,” said Loyce Pace, executive director of Global Health Council. “We want to also ensure that there are resources put behind it, because there’s this kind of a mismatch between the rhetoric and the reality.”

A role for aid

Existing agreements to finance universal health coverage in low- and middle-income countries have not yielded strong results, according to Jacob Hughes, senior director of health systems at Management Sciences for Health. Few African countries have met the goals laid out in the 2001 Abuja Declaration, for example, which called for at least 15% of national budget allocations to health care.

“Should the declaration be accompanied by commitments to spending? Well, it could be, but there are already commitments to spending out there. The reality is that countries can sign up to those commitments, but they do not necessarily materialize,” Hughes said.

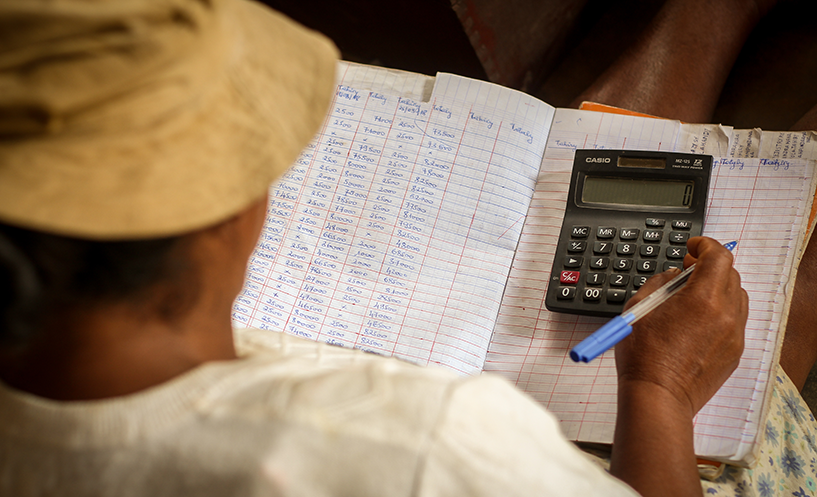

Hughes explained that there are three primary sources of health financing: government revenue, foreign assistance, and household spending.

“Amongst these three ingredients, countries come up with their own formula based on how much they have of each, and it is frankly an insufficient amount of funds. The burden is usually picked up by households and it is monitored or tracked in terms of the extent to which they are exposed to catastrophic health care spending,” Hughes said.

The latest World Bank report on health financing for UHC, launched during last week’s G-20 health and finance summit in Osaka, Japan, found an estimated 3.6 billion people globally are not receiving the most essential health services they need. In addition, 100 million people are forced to pay out of their own pockets for health services. Out-of-pocket payments are particularly high in countries with very low per capita spending, which averages $40 per person in low-income countries, according to the report.

There is a role for international aid in this challenge, Hughes said, but not necessarily to solve UHC. Aid can sometimes serve an ultimately counterproductive role of “crowding out” domestic spending on health care, Hughes said.

“Aid is not going to help achieve the global health goals. It has to come from domestic spending. But aid is very important for purposes of equity and that the poor do not get left behind,” Hughes explained.

UHC is also not always guaranteed in some high-income countries. In the United States, for example, which spent nearly 18% of its gross domestic product on health care in 2016, more than 28 million people did not have any health coverage in 2017.

Meanwhile, Finland has had a universal health coverage policy for years, said Päivi Sillanaukee, permanent secretary at the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Helsinki. But the country’s aging population, combined with low birth rates, could threaten this coverage in the long-term.

“Our system is a welfare society where in our constitution there is [a] right for everyone who lives in Finland, that he or she gets free education, all the services and support, all sorts of social security they need for a good life. And that is then paid by taxation,” Sillanaukee told Devex in May.

“And in the future, when [the] population is aging, of course the demand for services is increasing. So we have to be very efficient [in] our system.”

After financing comes accountability

Governments are negotiating the final UHC agreement through July, in the lead up to the September 23 high-level meeting at U.N. Headquarters.

Global Funds’ Sands cautioned that the discussion of UHC, as a single item, is shortsighted.

“It is not just about getting rid of this or that disease … it’s about providing a comprehensive set of health services in a truly universal fashion. It is easy to leave people behind and we need to make sure it is the most vulnerable, the most marginalized that get picked up and cared for in the journey to UHC,” he told Devex.

Civil society organizations monitoring the progress on UHC want political commitments and political will, but also some form of mechanism to hold leaders accountable, Pace said.

“I think sometimes there’s resistance in these political meetings and dialogues to be too prescriptive,” Pace said. “And so I think you’ll see that resistance to metrics and targets, beyond what’s already in the SDGs possibly for that reason. However, we still need to, I think, bring in some of those concrete sort of directives for the way forward.”

She notes however that the work doesn’t end once governments agree on a political declaration. The real work needs to happen after — and sooner rather than later, she said.