Go To The People: Celebrating 50 Years at MSH

Go To The People: Celebrating 50 Years at MSH

Help us celebrate MSH’s 50th birthday! We were incorporated in Massachusetts, USA, on May 21, 1971 and have since then worked in over 150 countries. To celebrate our 50th, we invite you to follow our Go To The People series, sharing stories and reflections from current and former MSHers, partners, and local health leaders worldwide, as they reflect on the impact we’ve made together on the lives of individuals, communities, and in global health. Working together, let’s shape the next 50 years for greater health impact.

Cristina Maldonado, oficial de M&E de MSH en Guatemala:

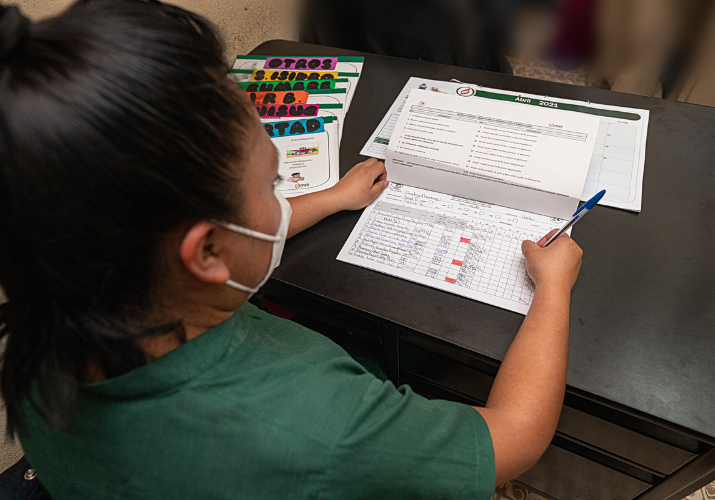

La primera vez que mostramos al Ministerio de Salud las últimas tasas de cobertura de visitas de atención prenatal, fue muy impactante. En ese momento, la mitad de las mujeres regresaron para una segunda visita después de la primera. Un tercio regresó para la tercera visita, y muy pocos regresaron para una cuarta. Cuando se dieron cuenta de lo que les decían los datos, se comprometieron a mejorar la situación. Se puede recopilar una gran cantidad de datos de salud reproductiva, y lo hacemos aquí en Guatemala, pero si no pueden procesar, consolidar o analizar esos datos correctamente, están volando a ciegas. Estos datos nos orientan y dan cobertura de la población, sin embargo hay otro elemento que también es imprescindible incluir.

Lo que más importa cuando uno trabaja para mejorar la salud de las mujeres y los niños en su comunidad es asegurarse de que tengan acceso a servicios de salud de calidad. Pero medir la calidad es una dimensión completamente diferente. Los procesos de calidad toman tiempo para medir y ver resultados, en donde la usuaria esté satisfecha, por eso digo que a veces la opinión de una mujer, aunque sea una sola voz, puede ser mucho más valiosa que, por ejemplo, mil puntos de datos. Es así como debemos abrir espacios para la discusión con las mujeres.

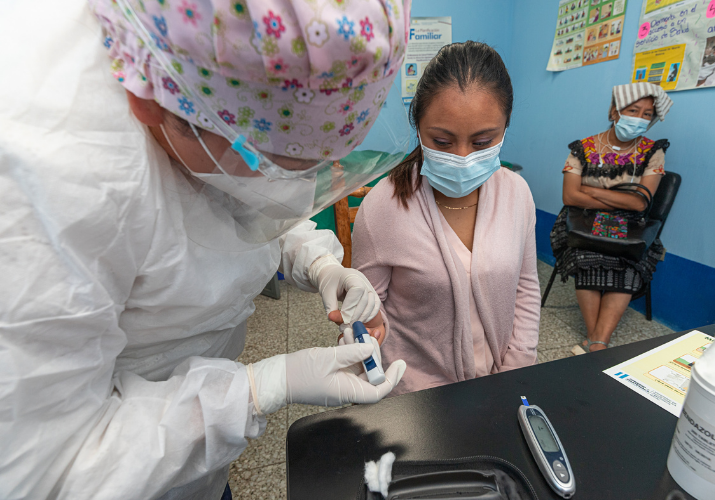

Cuando comenzamos a reunir a las mujeres en grupos de atención prenatal para tratar de mejorar la retención en las visitas de atención prenatal y mejorar sus resultados de salud, vimos la necesidad de fortalecer las habilidades del personal de salud. Los datos nos dijeron que el personal de salud no estaba proporcionando pruebas de glucosa u orina a las mujeres. Así que trabajamos para tener tiras reactivas en sus manos y, en ese mismo momento, preparamos un tutorial para el personal. Una prueba tan simple que puede darnos tanta información sobre el embarazo de una mujer. Especialmente en los puestos de salud remotos, realmente pueden marcar la diferencia. Esta es una intervención relativamente pequeña pero estamos mejorando, con pequeños insumos, con conocimiento aquí y allá, la atención a la salud de la mujer. Un sueño que tengo es ver un mejor seguimiento y atención para cada mujer en su atención prenatal en Guatemala. Para mí es muy importante que algún día, cualquier mujer que acuda a un centro de salud sea llamada por su nombre, sea bien evaluada y reciba uno o dos laboratorios que son básicos e importantes para ver cómo está progresando su embarazo, y pueda convertirse en una madre saludable.

Cristina Maldonado, M&E Officer for MSH in Guatemala:

The first time we showed the Ministry of Health the latest coverage rates of prenatal care visits, it was very shocking. At that time, half as many women would return for a second visit after their first. A third would return for the third visit and very very few would return for a fourth. When they realized what the data was telling them, they made commitments to improve the situation. You can collect vast amounts of reproductive health data – and we do here in Guatemala – but if you aren’t able to process, consolidate, or analyze that data correctly, you’re flying blind.

What matters most when you are working to improve the health of women and children in your community, is to make sure they have access to quality health services. But measuring quality is a whole different dimension. Quality processes take time to measure and see results, so that’s why I say that sometimes a woman’s opinion – although it is only one voice – can be much more valuable than, for example, one thousand data points. It is in that way that we must make room for discussion with women.

When we started bringing women together into antenatal care groups to try and improve retention to antenatal care visits and improve their health outcomes, we saw the need to strengthen the skills of health personnel. The data told us that health staff were not providing glucose or urine tests to women. So we worked to get test strips in their hands, and right then and there, set up a tutorial for staff. Such a simple test that can give us so much information about a woman’s pregnancy. Especially at the remote health posts, they can really make a difference. This is a relatively small intervention but we are improving, with small inputs, with knowledge here and here, the attention to women’s health. One dream I have is to see better prenatal care for all women in Guatemala. It is very important to me that someday, any woman that goes to a health facility will be called by her name, be evaluated well, and receive one or two labs that are basic and important to see how their pregnancy is progressing.

Monita Baba Djara, M&E Director at MSH and Senior Principal Technical Advisor for Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning for the Health Systems for Tuberculosis (HS4TB) Program:

When I arrived in Cameroon, I was the only English-speaking mental health professional in the country. With significant cultural stigma and fear surrounding mental illness, the need was truly overwhelming. Psychiatric or psychological resources were limited and unavailable in most areas of the country. Having worked as a marriage and family counselor and psychotherapist in the United States, I started a private practice which I ran for about ten years, working one-on-one with individuals and families in Yaoundé and Douala. I also worked at a dental clinic and traveled with a mobile clinic as there were so few dentists working outside the capital city at that time. The burden of people suffering from untreated oral health and mental health issues was significant and very much neglected. I remember the great relief in the eyes of women living in rural areas when we were able to remove teeth that had broken down leaving only exposed roots. Realizing the burden of pain they had been living with for years was overwhelming as anyone who has ever had a tooth-ache can attest to. The chief of one of the Bamileke villages in western Cameroon, where we ran dental clinics, wanted to adopt me as his daughter. He gave me a title of honor and a piece of land to build a home on when I retire. Being accepted by the chief, his family, and the village in this way was a profound and very humbling experience. At the same time, I knew that what I was doing was really a drop in the bucket. I wasn’t helping overall because the system was so broken and inadequate for addressing oral and mental health needs. Realizing that there must be some way to be a part of longer-term, sustainable change pushed me to find ways to be involved beyond treating individuals and to look at systems and capacity for change.

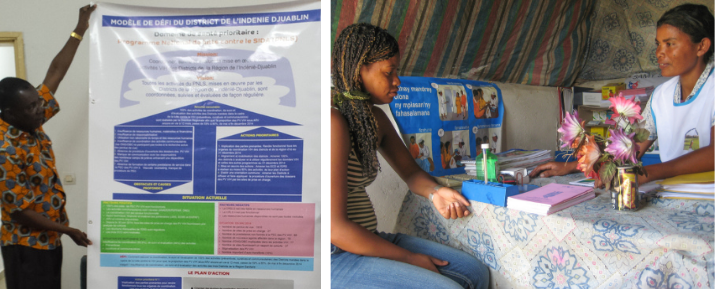

There is so much capacity to solve problems and a wealth of knowledge at the grassroots level. So, my whole career, I tried to be supportive and come alongside the people who are really doing the work at the community level or the health facility level. When I was helping to manage hospitals and community organizations, it became apparent that one of the major issues was really management and governance. It wasn’t so much that there was a lack of resources, yes there was a lack, but it really was about how those resources were managed—how to use health care resources, human resources, and manage the supply chain, all of which are the things we look at on a health systems level. All these lessons learned in my early career helped to shape how I approached more recent work—such as leadership and management development for postpartum family planning services through the Leadership, Management, & Governance (LMG) project or building the capacity of community health workers to collect and use data to improve the quality of their services in Madagascar.

It felt like we were always running blind when trying to make decisions to improve the performance of a hospital. We never had the data that we needed because most of the data being collected was about disease burden. But it wasn’t very helpful when trying to improve the performance of a hospital. I started to get into hospital performance measurement and measuring systems outputs. That is when I became more interested in the data side of the house. In Cameroon and Ghana, we worked on participatory hospital performance assessment. It was amazing to see how the power of teaching health professionals how to identify the data they needed to measure their performance led to a sense of responsibility for fixing the problems. External assessment of performance can lead to defensiveness and a lack of ownership of the results, but as one health professional said, “we chose what to measure and collected the data. We cannot argue with the results, now we have to do something to fix it.” We need practical data for decision making and management. Until you have the evidence and the proof, it’s really hard to engage resources or do any kind of advocacy. I’m not someone who loves crunching numbers—I’m more conceptual and interested in theories of change and how to measure change—but data is such a fundamental piece of what we do. There is such power in data.

Mercy Victor Bassey, Officer-in-Charge at West Itam Primary Health Centre, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria:

The most important part of my day is when I’m helping people who are sick recover—when my work puts a smile on someone’s face.

I’m proud of the improvements we’ve been able to make here at West Itam Primary Health Centre. We accept everybody. One of the things that can drive patients away from seeking health care is the attitude of the health workers themselves. So, I train my staff on how to have good interpersonal relationships with our patients, and we have been able to help a lot of women who then bring their children here, too. They see that we follow the normal procedure of testing before treatment for malaria and other diseases, and that we give the appropriate drugs.

I feel fulfilled. I feel motivated to do more. There have been so many positive experiences that grew out of our work here. One story is very close to my heart: A child born at our facility was then abandoned. With no family, she would beg for money, living on the mercy of staff and the patients. I said to myself, “This child can become something.” I gave her some money to start selling goods to patients on the hospital compound, and she worked and saved that money. When she was old enough, I told her to apply for university at the College of Health Technology in Etinan, Akwa Ibom State. She passed her entrance exams, and I committed to becoming her sponsor. She graduated this past November as a Junior Community Health Extension Worker and now she serves as support staff in this health facility.

John Isaacson, founder of Isaacson Miller, Inc. and Board Chair of MSH:

I have come to believe that learning and accomplishment are functions of courage, not of anything innate; and that courage is a gift, from your family or your friends or your teachers, and is something you earn, sometimes from your own cowardice. In my case, I got both courage and fear from my family. My mother was a smart and empathetic woman. She survived Auschwitz, at one point defying [Josef] Mengele. My father, an American soldier and OSS spy, was fearless. [The OSS, the Office of Strategic Services, operated during World War II and was the predecessor of the modern CIA.] At 5 feet 4 inches tall, he would jump into any adventure you put in front of him, no matter how much or how little he knew about it. And he often didn’t know anything about it; he would just feel his way through, but that didn’t bother him in the slightest. He liked learning on the fly. You carry these things with you. You jump into some things. You are afraid of others, but you jump anyway.

Over 39 years, I built a business. It wasn’t so simple, and it was a strange business to build, but it works. We recruit exceptional leaders for civic institutions, sometimes august, sometimes small, all mission-driven. We are an institution. It will, I think, endure. It has a mission and a future, and I’m not in charge of it anymore. The next generation runs it. Owns it. Literally. I understand the business of working hard to build something important and then not be at the front and center. When you do that, you shift from doing your own work to doing other people’s work. For a long time, my father didn’t understand what I did, but eventually, before he died, he got it. The world is in an era roughly like the one between 1871 and 1914, after the Franco-Prussian War but before World War I. Highly unsettled, highly prosperous, full of ideological contention, and probably ill-prepared politically and intellectually for what is coming. Even so, we have more opportunities than ever to make the world and the world’s health significantly better. MSH’s attempt to intervene in health care in such a marvelous array of countries is, I think, an act of courage. That’s admirable. Now, we have to match it with an act of both humility and intelligence. We have the right mission. We have the right history and the right people. Our job is to be useful to the future.

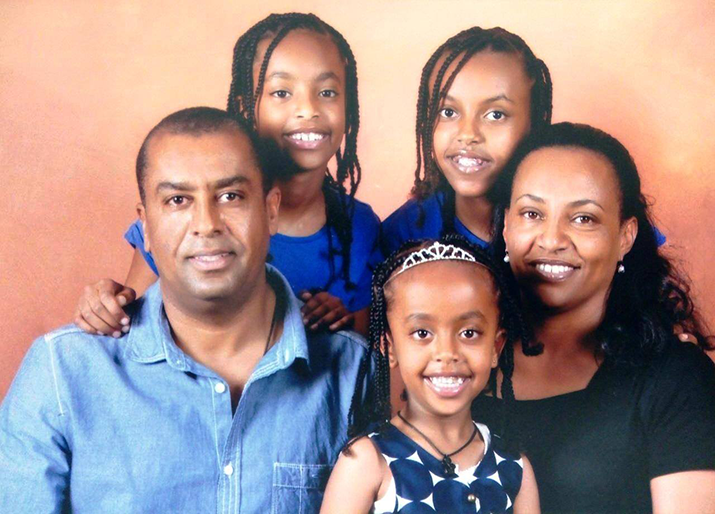

Berhan Teklehaimanot, former Communications Advisor for MSH in Ethiopia:

I didn’t know as much about HIV or TB at the time. I was new to the job, a communications officer with MSH for a health program in my home country, Ethiopia. It was the first person I met who really impacted me. Her name was Mulu. She was HIV-positive. We went to her house to interview her for a story. She was a sex worker and was living in a one-room house. You could barely fit two adults in that space and yet she had three kids living with her in that room. By that time, I had two kids of my own. I started to cry on the spot. She cried with me. I didn’t know whether to hug her or not. When I got home, I told my husband, “I’m done with this job, I can’t go back.” But I went back the next day, and I took down her story. I was sure she was going to die, but I gave her my phone number. A couple of months later, she called me and said, “I want to see you.” I went back to her house and I couldn’t believe it. She had gained 5 kilos, and her body was gaining strength. When I saw her, I just saw hope. That’s all I can say. Hope was in her face and hope was sort of gluing my heart together. All the efforts our project had made were really helping this woman. From then onwards, whenever I meet people who have recovered from diseases such as TB, HIV, malaria, and so on, I try to find out what they need and find ways to help them. I have a group of friends who donate their kids’ clothes, lunch boxes, or help to pay school fees that year. Even the smallest bit of help or act of kindness is important.

My dad only had two girls, and in Ethiopia, that’s not common. Whenever people asked him, “Aren’t you going to have a boy?” he would say, “What for? I have two strong ladies, that’s enough for me.” I learned from him to be very assertive about speaking up for myself. It’s not about being equal with men; it is about being equal with myself. I don’t need to compare myself with women or men. We are each made differently and we each bring a unique flavor to the world. I want to embrace the gifts and talents that are unique to me and use them well. When we try to compare ourselves with others, we miss out on being the best we can be.

When I interviewed for a communications job with the Eliminate TB project (an MSH project), they asked me what my strengths were. I told them being a woman is my strength. We see the world in such a different way that men cannot imagine. I get up in the morning, make sure that everyone has a good start to the day, that they are all well-fed, in a proper uniform, and happy. I make sure that my husband is ready for the day as well. When I get to work I’m just as focused, tackling challenges, addressing issues, and making sure that everyone connects. At the end of the day, I pick up my kids from school. I am a maid, a chauffeur, a consultant, a doctor, a referee, a judge, a counselor, and the next day, back at my job, I deliver. So when you talk about a woman’s strength, where do you start? And where do you stop?

Steve Solter, former Technical Advisor for MSH in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Indonesia, and the Philippines:

Working with MSH was really my first job in public health. I started in Afghanistan back in 1976 when I was 28 years old. MSH had just two projects overseas at that time: Afghanistan and Nepal. It really felt like a family. I was living in Kabul, where I met my wife, and we were married there. She was a nurse midwife who had been evacuated from Eastern Ethiopia while working with British Save the Children. Their clinic was overrun with guerrillas, and she was sent to Afghanistan. This was before the Soviet invasion, and things were quite safe there then, but it didn’t stay that way for long. For more than 35 years, I provided mainly long- and short-term technical assistance for MSH and our programs.

In 1990, I began working in the Philippines as a child survival advisor for a health program there. At that time, we were working with the Department of Health to plan the country’s first National Immunization Day, and our advice was to include only oral polio and vitamin A for the first round. Vitamin A could easily be given to children at the same time: a capsule squeezed into the child’s mouth with no need for needles, syringes, or advanced training. But Elvira Dayrit, who was the head of Maternal and Child Health for the Department of Health, said no. She wanted to vaccinate kids with everything at the same time: DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus), BCG (bacille Calmette-Guerin), and measles. I told her that I didn’t think it was going to work: “It’s hot out there. You’ll have mothers with crying babies waiting in lines for hours to get all the vaccines. It’s going to discourage them from coming back in the future. It’s going to be a setback.” But she was adamant: “Trust me. We’re going to do it.”

And she was absolutely right—when I went out to observe on Immunization Day, the women at the village level had organized everything so well, with tens of thousands of volunteers. They pulled it off perfectly, without the long lines or the long waits. Dr. Dayrit never mentioned how wrong I had been—it was just another day’s work for her. It was fantastic to watch and, more important, a clear demonstration that local people (especially women at community level) have a much better understanding of what’s going to work and what isn’t. And for me, and in any technical assistance role, you have to learn to listen and then learn as you go along. It was terrific to see the annual vaccination campaign improve and expand over those years, protecting many hundreds of thousands of children from illness and death.

![[A village map used in the La Union province, Philippines, shows which households have fully immunized children, which are using family planning, etc. These kinds of data boards were used to plan our immunization campaign at the village level in 1992.]](https://msh.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/village_board_715px.png)

Dr. Ann Phoya, Deputy Chief of Party for the USAID ONSE Health Activity, Malawi:

It was my first job after returning home to Malawi, having just completed my PhD in the U.S. It was 1994 and Malawi was designing its first Safe Motherhood program, specifically addressing issues around maternal mortality. As the Safe Motherhood coordinator starting from zero, I knew the first thing that we needed in place was political commitment, so I managed to secure an appointment with the First Lady. I asked her to become an advocate for safe motherhood in the country because I thought she—as a woman married to the head of state—could carry our information to the top levels of government, without me having to write a memo that may get lost in the bureaucracy. The First Lady agreed to assist us, and soon after that we saw the head of the state begin making statements as he went out to meetings—statements such as ‘let’s take care of our women, let’s put a bit more resources here, let’s be more respectful of women in our country.’ At that time, Malawi’s fertility rate was very high, around 7.6, which meant women gave birth to about 7 children throughout her life. At a public meeting, the head of state at that time specifically told the men to ‘put on the brakes’ to help reduce this fertility rate. He meant—of course—using family planning, so at that time I felt very motivated and saw that I had spoken up and convinced people that we really needed to put resources towards improving the health of women and children.

Over my career, I’ve learned to speak my mind and to speak the truth. My father was someone who spoke his mind when he felt that people needed to know something, and I think it was because of his passion for education that he encouraged me to go to school and become a nurse midwife. When I was promoted to be Director of the Health Sector “SWAP”—also known as the Sector Wide Approach—one of my responsibilities was to coordinate utilization of a health fund, which pooled resources from government and development partners to make sure that we deliver a package of essential health assistance for the people of Malawi. My Minister of Finance at that time felt that the health sector had been funded adequately to do this, but I had to go back to his office and tell him that we don’t have enough money. I emphasized that our health workers—especially nurse midwives—were resigning probably one every two hours to go work in the UK where they could make a fair, livable wage, so one of the things we did at that time was to negotiate an increase in salary for health workers, and to make sure that we were training them in an appropriate environment. I advocated for the resources needed to increase the training space in our universities, improve our laboratories, and expand classroom space in the College of Nursing. We also negotiated that as soon as these graduates leave the school, they are immediately employed. We needed somebody to make a bold decision, and go there and make noise in the appropriate ears, so that people would listen. This is one of the things that I’m passionate about, and everything I pushed for happened.

Jude Antenor, Senior Associate for Information Technology at MSH, USA:

My passion for technology started when I was in high school, living in Haiti, where I’m from. A friend had introduced me to HTML, and soon I was spending a few hours a week at the cyber cafe in Cap-Haitien, my hometown. The cost per hour was 35 Gourdes (0.42 cents in today’s rate), which felt like a lot of money as a kid borrowing from his parents. I was amazed by how the Internet worked; how I could connect to friends outside of Haiti and all over the world. However, my interest quickly turned into desperation, as I did not even have a computer of my own. When I had the opportunity, I enrolled in computer science school. The journey wasn’t easy, but I was dedicated to achieving my goals. My senior year, I had an internship at one of the biggest tech companies in Haiti. I could see my future ahead of me. But in January 2010, the earthquake hit.

It was like the world had collapsed on my shoulders, and I could see my future and dreams under the rubble. Two months later, thanks to great leadership from my school’s staff, they reopened their doors. I continued with classes, although under extreme difficulties: no electricity or Internet. On top of that, I was sleeping in a tent in my front yard, as we were scared to live in the house, and badly shaken by the earthquake. But I couldn’t allow these hardships to stop me, and I obtained my bachelor’s degree with honors in October that same year. I am conscious of all the effort that people from different fields make every day to make the world we live in better and safer. I also believe it can’t be achieved without technology. My colleagues at MSH have always encouraged me to keep pursuing my goals and in 2020, I started a masters degree program. Through technology, I want to play a part and make an impact. I know it requires a lot of sacrifices and dedication, but I am up for the challenge.

Alaine Umubyeyi Nyaruhirira, Principal Technical Advisor for Laboratory Services at MSH, South Africa:

I was among the first few waves of young Rwandans who decided to return home after the 1994 genocide and the end of our civil war. I joined the National University as a lecturing medical biologist. I started to see people who were very sick: young people, returning members of the army, survivors of the genocide. My friend, who would become my husband, told me ‘it’s not just poverty and poor nutrition, these people have HIV, and many have TB.’ I knew about HIV, of course, but to put the name of that disease onto your people—people you know—was devastating. The health system was in tatters. Treatment was not in place, and my colleagues and I watched helplessly as many suffered, withered slowly, and died. I decided to start working with our community at the university to teach them about sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, so I formed the first club of young people to talk about this issue. I was a young lecturer, 26 years old, and so those around me were quite shocked.

They didn’t expect to see a young woman teaching about sexual health, a topic that’s somewhat taboo in our culture, but I was confident in the skills that I had. I worked with a clinician to provide teaching materials for my discussions. In my microbiology courses, I started to teach about HIV transmission and how my students could protect themselves. My husband had just become the head of the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali, and we had to move to the capital. Looking at this crisis, he felt strongly that the solution would be to fund treatment, strengthen the health system, and have good diagnostics in place. Already having a background and interest in health technology, I committed myself to studying medical sciences and helping to build diagnostic capacity for HIV and TB in Rwanda.

It was not common at that time to see a woman go for a PhD, especially outside of the country, and there was pressure to take care of my responsibilities at home, but my husband—who had become the State Minister of Health—told me ‘you need to go to school because it’s you who will help our country and family later.’ I completed college at 17, the only woman in my graduating class that year. My father had been a medical doctor; growing up, I envisioned a similar career for myself. But, because my family had been living as refugees in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, I didn’t have access to the department of medicine, and so I studied biology instead.

Access: that’s my dream

When I look back to 1994, when we were starting to rebuild the health system, we would not have believed that testing and treatment for HIV would become so accessible. The first lab that I worked in had just three microscopes. From 2000 to 2012, I worked with Rwanda’s Ministry of Health to build our national reference laboratory’s, as well as East African regional level’s, capacities for diagnosis of TB, HIV, malaria, and other diseases. Today, ten years later, of course the same labs can do nearly any kind of test, from HIV and TB to diabetes to types of cancer, and many hospitals have the same diagnostic testing capacity and resources. The speed of diagnostic development is amazing, but my first wish is to see greater equity in diagnostic access. Even within a country, some populations do not have access to basic diagnostics. Access: that’s my dream.

However, the current pandemic shows us again and again that we have a broken and unsustainable global health system, with weak diagnostic capacity that no longer protects the world against future diseases and deadly epidemics. Together, with my colleagues, I am proud of the work we are doing to build laboratory capacity across the world. I am determined to be part of the fight against TB, HIV, malaria, other chronic diseases, and epidemics such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, with the hope to see their eventual elimination.

From South Africa to Afghanistan

2017 was the first time I went to work in Afghanistan. I went from South Africa where I now live, and I was a little afraid, and then I was so struck by how kind and resilient the people were, just like Rwandans. Afghanistan has a similar story to Rwanda after the genocide: so much insecurity, instability, and a health system that had been badly damaged years ago. I was the only woman in the office at the time, and I had to take care to cover myself with the appropriate clothing. I had to respect their religion and customs, and yet I have my own culture that I wanted to be recognized and respected.

I’m the eldest in my family—and most of my siblings are men—so at an early age I learned how to negotiate with men, but another issue in Afghanistan was my skin color. The first time I met members of the Ministry of Public Health, they were very curious and a little bit suspicious of me; it’s very uncommon to see black people there. At the first training on GeneXpert MTB/RIF—a new diagnostic tool to detect TB and Rifampicin resistance—there were 60 people in the room, all of them men, and my first observation was this gender imbalance. The first question I often received that first year there was about my PhD: How had I reached that level of education? Why was I doing this work? Yet, as I told my story, these colleagues and trainees would often ask to take a photo with me, so that they could show their wives and daughters that there are women like me who travel and teach. I took that as a huge compliment.

At the end of my first mission to Afghanistan, the Minister of Public Health and TB program director organized a reception and presented me with a gift of three beautiful necklaces. He thanked me and requested that I return and continue our work together. Even now, my Afghan colleagues ask me when I will be coming back to see them. We are very proud of the work we’ve achieved together under the USAID-funded Challenge TB projectto introduce faster, more accurate diagnostic tools in labs across the country to help fight TB. I want to add that four years later, since that first trip in 2017, there have been drastic changes with the new leadership in Afghanistan, which has started to promote access for women in all levels of the state and in education.

What’s next?

On the African continent in particular, I would like to see many more female graduates in universities—both in their home countries and abroad—return to take up leadership in all levels of the health system. I’m grateful for the opportunities I’ve been given during my career, opportunities from mentors in my PhD program to the different organizations I have worked in. To give back, I am a co-founder of Pan African Women in Health [PAWH], which advocates for and mentors young women in my field, and in sciences in particular. PAWH brings together leaders who are passionate about a common goal: increasing networking and improving women’s opportunities to be the next generation of female African leaders, who need to be included, heard, and valued.