MSH Joins with Mott MacDonald, ICF to Take on Stubborn Diagnostic Gap Problem

MSH Joins with Mott MacDonald, ICF to Take on Stubborn Diagnostic Gap Problem

What do you do when you have a laboratory full of shiny diagnostic equipment but none of the consumable supplies needed to run it? Or when you have plenty of reagents and other consumables but not enough skilled personnel to use them? Or how about when you have all those things but most of the equipment, consumables, and staff training were designed to test for one disease and you are facing an outbreak of another?

These are the types of questions being asked by low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) worldwide—many of which rely heavily on donor funding for health-related investments, including in laboratory services.

They were also questions at the heart of a recent technical forum in Washington, D.C., where a group of health system experts and policymakers met on Jan. 30, 2024, to discuss why less than half the people around the world still have little or no access to basic diagnostic tests and, more importantly, what can be done about it.

The upshot of it all? It’s not enough just to focus investments narrowly on addressing specific diseases or conditions. What the countries facing such challenges are lacking is the robust and resilient laboratory systems required to effectively and holistically serve the needs of both patients and health systems.

The technical forum was hosted jointly by Mott MacDonald, Management Sciences for Health (MSH), and ICF in conjunction with their launch of a technical report on addressing the shortcomings in governance and integration, sustainable financing, laboratory workforce, and infrastructure that persist in many LMICs.

That report—“Why laboratory investment matters: Rethinking the role of laboratory services in global health”—noted that progress has been “fragmented and slow” since a Lancet Commission in late 2021 issued key recommendations for eliminating barriers that were keeping 47% of the population worldwide from accessing basic diagnostic tests.

The Lancet Commission on Diagnostics said an estimated 1.1 million premature deaths could be prevented in LMICs annually if 90% of patients had the tests they need for just six priority conditions—diabetes, hypertension, HIV, and TB in the general population and hepatitis B and syphilis in pregnant women.

“The economic case for such investment is strong,” The Lancet Commission said. “The median benefit-cost exceeds one for five of the six priority conditions in middle-income countries and exceeds one for four of the six priority conditions in low-income countries.”

But even though two years have passed since The Lancet Commission made its recommendations, the report said, “the continued inadequacy of diagnostic services in low- and middle-income countries puts everyone at risk.”

Why is the needle moving so slowly?

Although they are vital for diagnostic testing, disease surveillance, and global health security, many laboratory systems still lack the funding and continuous resourcing they need to operate effectively. Moreover, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and related comorbidities are posing an increasing burden on health systems in general and call for taking a more holistic approach to laboratory strengthening.

One problem, according to the report, is that countries often don’t have governance structures that place a priority on ensuring equitable access to medical laboratories. The report noted that only 55% of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa’s 47 member countries had Ministry of Health laboratory services directorates or divisions as of mid-2023. Dedicated units with high-level political support are vital for improving the integration of laboratory services within the broader health system.

According to one of the report’s authors, Dr. Alaine Nyaruhirira, Principal Technical Advisor for Laboratory Systems at MSH, lack of leadership is the first gap that must be filled because having a directorate of laboratory services “can raise the voice of lab professionals very high at the ministerial level.” Establishing such leadership “can help us learn to remove the other barriers,” she said.

Another problem is that most laboratory investments focus on addressing a single issue or a narrow set of diseases and provide little or no funding for other vital laboratory services. Such siloing can mean that investments become unsustainable once the donor funding cycle has ended and that different laboratory services lack coordination and integration.

“All the funds that are coming to support diagnostic and lab strengthening are donor oriented, which means that the donors are coming with an agenda,” Dr. Nyaruhirira said.

Shortages of trained laboratory personnel have also contributed to the slow progress being made—shortages that often are caused by low pay and a lack of career advancement opportunities, the report said. It further noted that outdated and inadequate infrastructure, including communications networks, utilities, roads, and transportation services, likewise limit laboratory capabilities.

Is laboratory strengthening really so important?

In many LMICs, particularly in remote areas, testing facilities are scarce or nonexistent and illnesses often are treated empirically. Unfortunately, antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—a global threat that The Lancet estimates was directly responsible for 1.27 million deaths in 2019—is caused in part by treating sick individuals with antimicrobial agents without knowing whether their illnesses are a result of microbes that are susceptible to those agents.

Ensuring that health care providers have access to laboratories equipped to test for a wide range of pathogens can go a long way toward ensuring that the right medication is used at the right dosage for the right amount of time, thereby helping to reduce the incidence of AMR.

Laboratory services strengthening can also improve a country’s ability to detect emerging or re-emerging AMR threats by ensuring that its health workforce is skilled in surveillance for infectious diseases, the report said. Well-trained surveillance teams and well-equipped laboratories similarly are crucial for detecting diseases with epidemic potential, such as COVID-19.

The holistic approach to laboratory systems strengthening also involves broadening the scope of testing and securing more funding for addressing NCDs. The report noted that most investments are focused on combating specific diseases such as HIV or TB and largely ignore conditions such as diabetes and chronic kidney disease, which require biochemical testing capabilities to diagnose and manage.

“There is often little to no provision of histopathology, endocrinology, or even basic blood chemistry services in laboratories,” the report said.

No matter what the testing is for, however, the best trained workforce with the best outfitted facilities can only do so much if patients and/or specimens can’t reach them, electricity isn’t available to run the diagnostic equipment, or test results aren’t rapidly and accurately communicated to referring clinicians or patients.

The authors of the report recognize that implementing a simple, reliable, and cost-effective laboratory network is not an easy task. Efforts by and strong coordination among all stakeholders—including human, veterinary, food, and water laboratories; universities; research institutes; and associated authorities, ministries, and donors—are essential for establishing a successful laboratory system.

To that end, the report issued a call to action that includes aligning donor funding with national health system priorities to address the siloing problem and providing clear career pathways and specialist training opportunities for laboratory professionals to address the workforce retention problem. It also urged policymakers to develop an investment case for national laboratory services, including costed delivery targets, and to plan services with a focus on reaching universal health coverage goals.

But while the world is still a long way from reaching the target set by The Lancet Commission of reducing the diagnostic gap for the six priority conditions to 10% or less, one thing in particular gives MSH President and CEO Marian W. Wentworth hope: Policymakers and investors alike are coming to recognize the importance of bolstering up the entire laboratory system.

“Momentum is gathering,” Ms. Wentworth said in addressing participants at the Jan. 30 event. “Collective willpower is growing, and I believe that if we can harness that energy, we can seize this moment to effect meaningful change.”

And as long as that trend continues, organizations like MSH, Mott MacDonald, and ICF will be around to help us get there. Together with other nongovernmental entities in the global health care space, these three organizations are all actively working in areas related to the technical paper’s call to action.

Mott MacDonald, through its partnership with the Fleming Fund, has been a part of efforts to help the African Society for Laboratory Medicine strengthen AMR surveillance, working with national AMR coordinating committees and governments as well as the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention to strengthen capabilities in this crucial area.

For its part, ICF is the lead implementer on the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Infectious Disease Detection and Surveillance Project, which operates in more than 20 African and Asian countries to improve diagnostic capabilities to detect priority diseases and AMR.

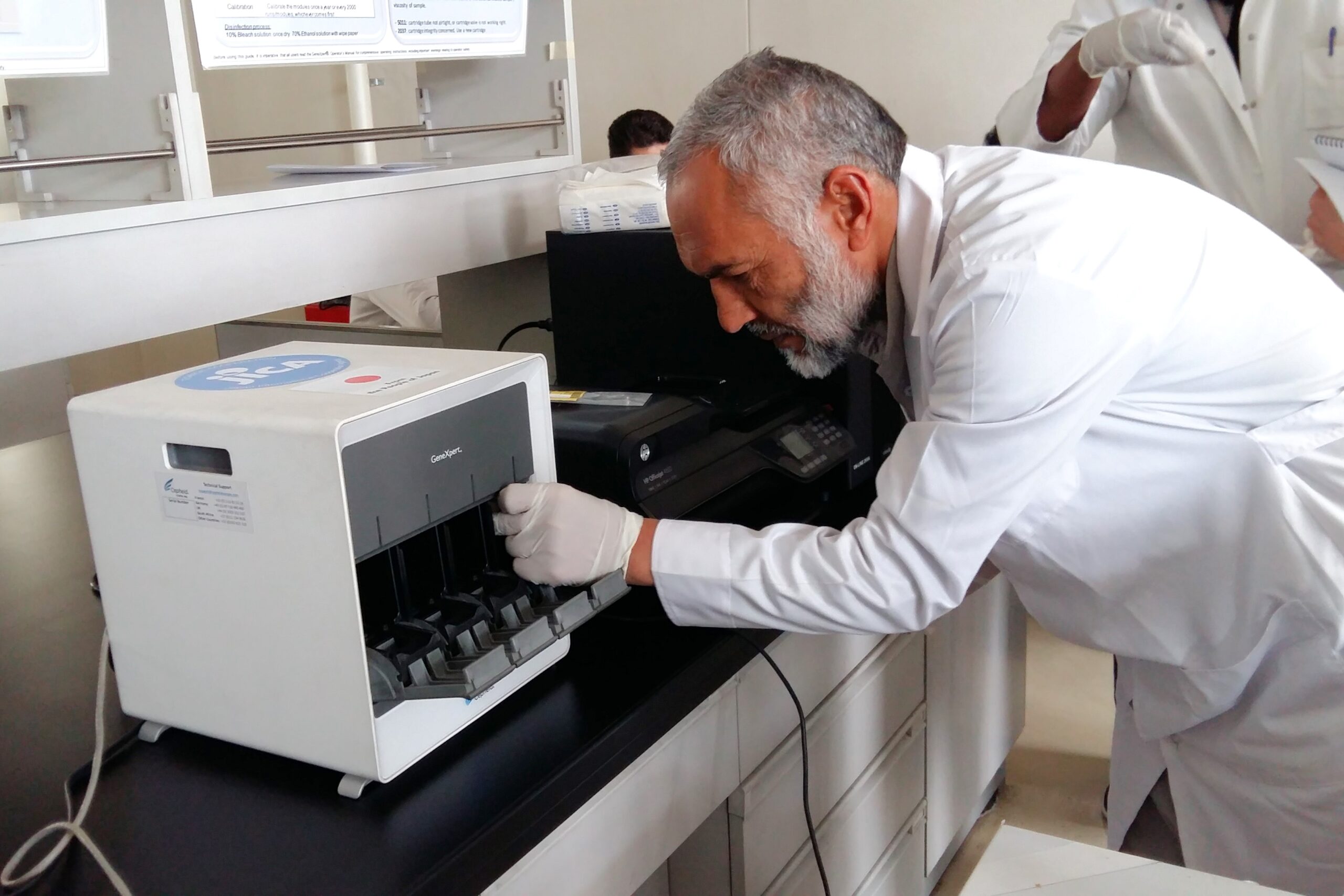

As for MSH, in addition to our longstanding work on laboratory strengthening, such as training laboratory professionals in project countries through partnerships with USAID and other funders, we are supporting efforts to expand diagnostic capabilities in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Madagascar, and other countries by helping them use GeneXpert machines to test for multiple diseases.