Boosting Vaccinations, Countering Disinformation: Using Meta to Fight COVID-19 in Benin

Boosting Vaccinations, Countering Disinformation: Using Meta to Fight COVID-19 in Benin

by Timothé Chevaux, Jean-Claude Lodjo, Méré Chabi Boum, Raphaël Gnonlonfoun, Alexis Bokossa, and Mathurin Alohou

From fake COVID-19 protocols to miracle treatments to cure cancers and other serious diseases, all too often we hear examples of social media being used as a tool to spread fake news. As communications and health experts in Benin committed to combating the threats posed by diseases, this is especially painful for us. We know how important reliable health information is, and we also know the opportunities afforded by social media to reach both large-scale and targeted audiences with that information. Misinformation has especially proliferated during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the opportunity to partner with Meta to launch a Facebook campaign to promote accurate information about COVID-19 was welcomed by all of us at the USAID Integrated Health Service Activity, led by Management Sciences for Health.

- We measured a lift in ad recall among different age and gender subgroups, which indicated that the ads were memorable, especially for women between 25 and 34

- We noticed that people were more engaged when they were watching video testimonies from people sharing similar experiences

- Our campaign gave us important information about what was and wasn’t working in how we communicate about the safety of vaccines—read more to learn about our experience.

Understanding the problem and how to address it

The seriousness of the mistrust of COVID-19 vaccines among young adults was confirmed early on during the campaign design phase: when examining COVID-19 vaccine uptake, acceptance, and hesitancy in Benin in summer 2021, we learned that on a representative panel of respondents, the rate of people who were planning to get vaccinated was barely above 50%.1

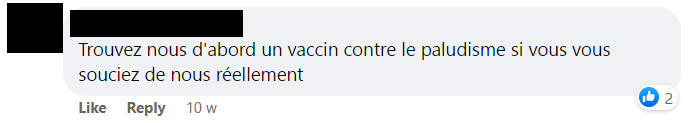

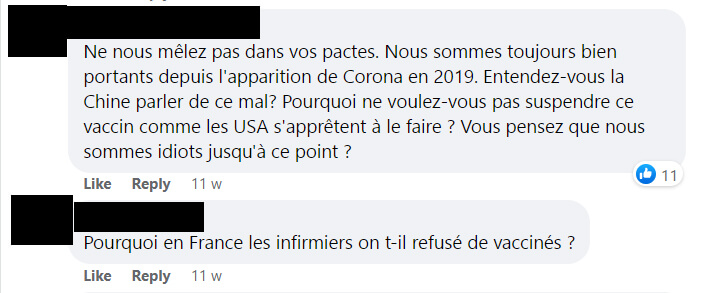

Our existing country presence and local contacts were key to understanding the reasoning behind this vaccine hesitancy. Based on discussions with Beninese health professionals and citizens during project activities, we learned that three main reasons were driving the phenomenon. First, for many people in Benin, COVID-19 wasn’t considered a serious threat in comparison to other diseases, such as malaria. Second, people didn’t trust the vaccine as they considered it to be inefficient at best and lethal at worst due to reports of rare cases of thrombosis with certain COVID-19 vaccines. Finally, misinformation and the spread of rumors was deeply detrimental to the willingness of the population to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

It was clear that our campaign needed to focus not only on helping people find centers to get vaccinated, but also on providing accurate and trustworthy information about the vaccine.

We launched our first campaign in September 2021. We focused on promoting the official Benenise website, where people could find vaccination centers in the country, and the targeted web pages from the World Health Organization’s site dedicated to responding to concerns related to adverse side effects.

From the comments, we could see that distrust in vaccines was prevalent: many Facebook users feared potential side effects from the vaccines and would share their fears in the comment section of our ads.

In terms of engagement, our ads were seen at least once by 218,476 people with an average of 5,495 unique link clicks per ad. We worked with Meta to run a brand lift study to measure how the campaign impacted our target audience’s confidence in the safety of available COVID-19 vaccines.

While the first three-week Meta campaign on Facebook did not see an overall lift in the number of people who were not concerned about side effects, we did measure a lift in ad recall among different age and gender subgroups which indicated that the ads were memorable, especially for women between 25 and 34.

The first campaign gave us important information about what was and wasn’t working in how we communicate about the safety of vaccines. For the next iteration of our campaign, we looked to better target our communications. In November, the Ministry of Health (MOH) tasked our existing project with supporting their mass vaccination campaign. This allowed us to align our messaging to complement a national effort, while also more efficiently addressing some of the most common concerns seen in the comments we received, including vaccine side effects for pregnant women—notably the very age group who had found the ads in the first campaign most memorable. We also looked to incorporate a different approach to engage our audience and created video testimonies of people who had just been vaccinated.

When it was time to look at our results, this creative iteration proved central to audience engagement: while other photo and video content that we posted received between 7,000 and 9,000 unique link clicks, with video testimony engagement leapt to more than 13,000 unique link clicks. During our second campaign, ads were seen on average at least once by 194,215 people, with an average of 7,514 unique link clicks per ad.

While we were unable to run a second brand lift study on our ad campaign, research shows that shifting people’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on vaccines through a single communication channel alone is challenging. The second campaign was run alongside a broad, multi-faceted national effort targeting vaccine hesitancy, which included communication interventions at multiple levels. Overall, during the period of our two campaigns and the national campaign in Benin, data relating to COVID-19 vaccination rates demonstrated significant changes in Benin: MOH data showed the number of people fully vaccinated rose from 0.16% in August to 11.06% by December, and, on a representative panel of respondents, the percentage of people hesitant to get the vaccine dropped to 10%, a 40-point drop since September 2021.

What did we learn?

What did we learn from this experience? Our partnership with Meta has been extremely valuable:

- The first lesson learned from this work was the usefulness of breaking the conversation vacuum. Thanks to Meta Audience Insights, it became easy to target the desired audience—those who might not get access to public health information—and also to reach those who had reservations about the vaccine.

- We learned that video is a much more engaging medium for Facebook users in Benin—our testimonial videos were of more interest to our users than stationary content.

- Although attitudes in Benin changed and many more people were vaccinated, more work is still needed. Many conspiracy theories were published as comments under our ads, including up to 418 comments on one ad alone, which is an alarming concern that needs to continually be addressed. It is important to invest time and resources into responding to conspiracy theories with accurate information.

- Our final call is the importance of building strong collaboration among different stakeholders. Our most successful campaigns happen where we are able to gather momentum with other partners and build upon national and local vaccination efforts.

- Carnegie Mellon University (US) and University of Maryland (non-US), 2022-01-13

Press Contact

Please direct all press inquiries to Jordan Coriza at jcoriza@msh.org or 617-250-9107