Fighting Malaria in Nigeria: Health Workers Harness Rapid Diagnostic Tests to Improve Care

Fighting Malaria in Nigeria: Health Workers Harness Rapid Diagnostic Tests to Improve Care

When Nigeria’s Ministry of Health produced new treatment guidelines requiring that all fever cases be tested for malaria, it fell to health workers such as Tabitha Osmau to turn this policy into action in health facilities across the country.

On a recent Tuesday afternoon at the Primary Health Center (PHC) Gura Topp in Plateau South Local Government Area (LGA) of Plateau State, Osmau is actively holding forth among a group of health care workers who gathered to talk about their experiences using malaria rapid diagnostic test kits (RDTs)—a fast and easy-to-use tool for malaria diagnosis that has been deployed across state health facilities.

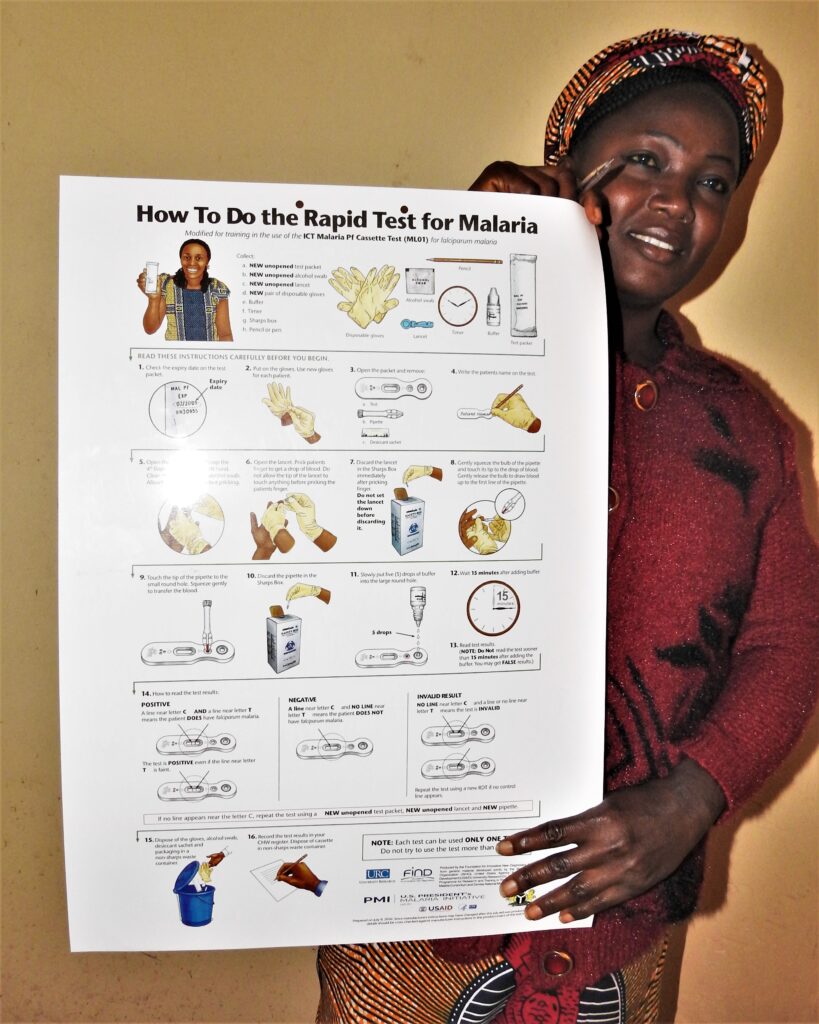

“The meeting is an opportunity to provide hands-on training and support to our colleagues on how to get the best malaria results using the RDT,” explains Osmau, who, like all health care workers and PHCs in Plateau State, is being supported by the US President’s Malaria Initiative for States (PMI-S) project with RDTs, RDT course materials, and job aids.

Nigeria, a malaria endemic country, accounts for a quarter of global malaria incidences, and RDTs are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a cheap, fast, and reliable way of properly diagnosing malaria. The use of microscopy, another recommendation by WHO, requires skill sets and infrastructure that are not readily available in most of Nigeria’s PHCs, so this leaves RDTs as the tool of choice. Anyone can be trained in a few hours to use them.

“It is the only means we have of testing for malaria,” explains Gloria Dem (pictured above), another health worker at the meeting from a neighboring PHC in Rayfield community. She asks the group for a demonstration on how to interpret the results from the malaria test kits because “it is a lifesaver in our health facility. We do not have access to microscopes or regular electricity to power them.”

Osmau sets up a workstation in the front of the room and invites Dem to demonstrate how she uses RDTs, with another health worker acting as a patient. The accuracy of these malaria RDTs relies on following correct procedures and the accurate interpretation of results, so encouraging health workers to explain and show each other how they use RDTs is something Osmau does all the time. “I want my colleagues to understand how human error can contribute to invalid test results,” she notes. “When they demonstrate RDT use in front of others, improper procedures are quickly detected and corrected, so hopefully they are not repeated at our health facilities.”

Dem next goes through the process for the group: She collects a drop of blood and adds it to the RDT cassette through one hole, adds the reagents through the other, and waits for 20 minutes for the results. For the next 30 minutes, Osmau, Dem, and the other health workers discuss the interpretation of the test results.

RDTs boost health workers’ confidence

Lyop Dachung, a community health worker at the PMI-S-supported PHC in Sharubutu, Riyom LGA, agrees with Osmau’s and Dem’s assessment of the benefits of RDTs: “[They] are fast and reliable and help me better support my patients. Most of those who come to me for treatment are farmers from the community, who can be impatient and want malaria medicine anytime they have fever. I use the RDT to quickly determine if they need malaria medication or not.” Dachung understands their impatience and their need to get back to work, but if they test negative for malaria, she refers them to a secondary health facility where the cause of their fever can be better determined.

Using RDTs also helps ensure that medicines are not wasted on diagnostic guessing. “Overall, the health outcome for our patients is good,” notes Dachung, and “RDT helps us diagnose quickly…and this is a big confidence boost to me as a health worker.”

PMI-S’ support for the use of RDTs by state health workers has been critical to correct diagnoses and maintaining the health of their patients. And, as Christopher Bewa, program manager with the Plateau State Malaria Elimination Program, explains, “One of our goals is to make malaria testing mandatory before treatment is provided, and we are pleased with the wide support we see among health workers in the state. PMI-S support has been vital [to these efforts]. We are working at the government level to sustain this work, which will make a significant difference in our fight against malaria.”

For Osmau, as for Bewa, it is a continuous push to translate policy for malaria treatment into concrete steps and processes at health facilities, whether for children, pregnant women, or other adults. “Our work at the front line is critical; we must quickly address skill gaps that will support actions for malaria elimination.”