Insights from Guatemala: Improving Indigenous Women’s Maternal Health through a Blended Model of Care

Insights from Guatemala: Improving Indigenous Women’s Maternal Health through a Blended Model of Care

By Jennifer Gardella

The highlands of Guatemala are home to vibrant indigenous Mam and K’iche’ communities that have unique customs and traditions, including when it comes to seeking maternal and newborn care. In these rural areas, traditional birth attendants, or comadronas, provide critical support to indigenous pregnant women and their families throughout their pregnancies, including antenatal care (ANC), childbirth assistance, and postpartum care.

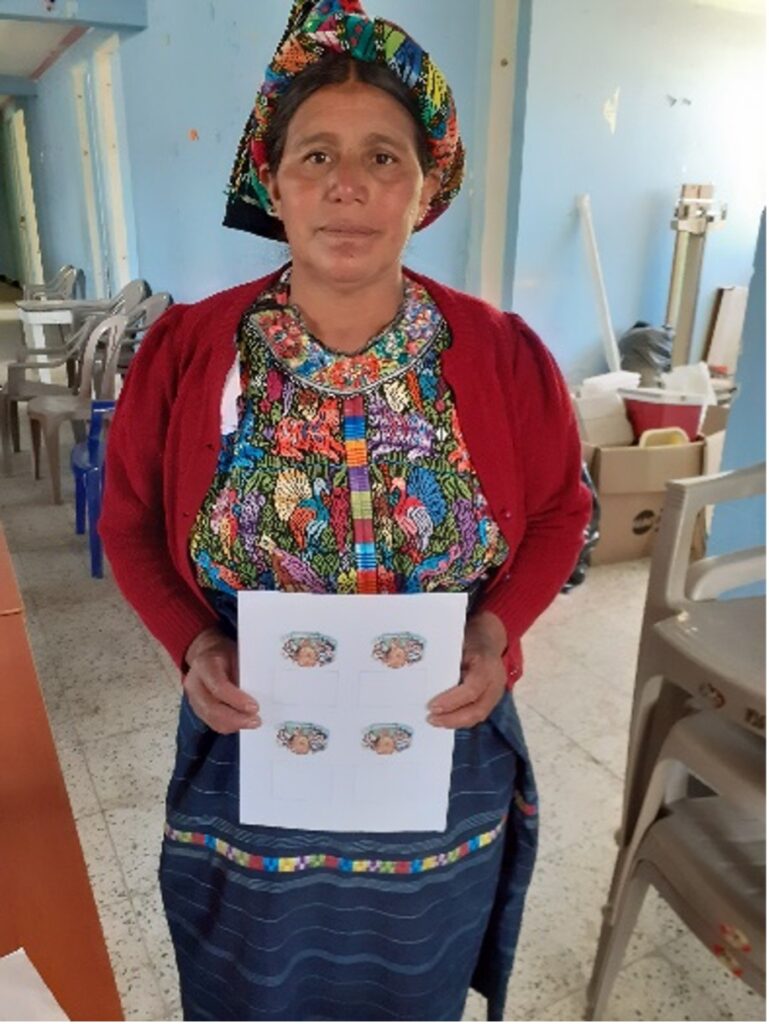

Maria,* a 55-year-old mother from Quetzaltenango Department’s Cajola municipality, has served her community as a comadrona for more than 30 years. She recalls the day when, from inside her home, she heard a woman screaming outside. “I went to help her, and I found her kneeling on the ground and complaining of severe stomach pains. I realized that she was giving birth. At that moment, I felt no fear.” Maria stayed with the woman during labor and helped deliver the baby. She has been supporting women in her community and guiding them along their pregnancy journeys ever since.

Comadronas like Maria serve as a key link between indigenous families and the health care system, with their collaboration with public health providers increasing significantly in recent years. However, there are still missed opportunities that can ensure traditional practices are linked with the formal health care system to improve indigenous women’s experience of care.

Exploring Indigenous Women’s Antenatal Care Experiences

To strengthen these links and ensure better access to ANC for indigenous women, Management Sciences for Health (MSH) is implementing the Healthy Mothers and Babies in Guatemala project, known locally as Utz’ Na’n, in the departments of Quetzaltenango and San Marcos. In addition to community-based interventions, the project also aims to generate evidence and learning through qualitative research conducted in partnership with the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala (UVG) to identify gaps and co-design policy and programming recommendations to improve the availability, acceptability, adequacy, and quality of ANC services for indigenous communities in rural areas.

A recent ethnographic study conducted by the UVG Medical Anthropology Unit explored how the complex dynamics of cultural practices and beliefs were impacting health care pathways to ANC and experience of care among indigenous women. From September 2022 to January 2023, the research team surveyed more than 1,300 people, including 317 pregnant women, 104 comadronas, and 906 Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance (MSPAS) workers. The findings make a compelling case for integrating traditional practices, including comadronas as key health care providers, in the national standards of care in order to strengthen Guatemala’s primary health care system and improve maternal and newborn outcomes for the most underserved women and communities.

The Role of Comadronas in Community-Based Antenatal Care Referrals

Of the more than 100 comadronas interviewed, all of them stated that they refer pregnant women to facility-based ANC at some point during their pregnancies. This rings true for Maria. “In my case, I refer all of the women I see to the health centers, since they have ultrasound capabilities there,” she shares. “Every month it varies, but on average I refer five pregnant women—sometimes up to eight—to the health center. I send them to get their iron and folic acid supplements, to check their blood pressure, and to see how the mother and baby are doing in general.”

Regarding facility-based childbirth, 28% of comadronas surveyed always referred women they served to health services or facility-based delivery care. Like most comadronas, Maria has worked with women who experience complications during pregnancy that have prompted her to refer women to facility-based delivery care. She recalled one woman who developed an abscess during labor. “I told the family that the delivery should take place in the hospital, and I managed to convince them,” she says. “The issue was resolved, and she was able to give birth safely, to a healthy baby.”

Trust in the Health System

Despite these high referral rates by comadronas and a generally high degree of confidence in the health system among indigenous women surveyed, most indigenous women express preference for seeking care from a comadrona over a facility-based public health care provider. Apart from affordability of ANC services at health facilities, the majority of pregnant women surveyed—84%—cited greater linguistic and cultural responsiveness of care as the primary reason for this preference. “Many [indigenous] families are afraid to go to the health centers because [the health care providers] do not view them well. They don’t feel well taken care of,” Maria explains. “The facilities are very cold, and many women feel ashamed because they are not provided with culturally appropriate coverings to make them feel comfortable.”

This hesitancy extends beyond facility-based ANC checkups. “During labor, women are often left alone for long periods,” she shares. “Their families cannot always come in and stay with them, and they do not have constant support like they do when they seek care from a comadrona.”

Making the Case for a Blended Model of Care

About 78% of pregnant women surveyed reported consulting both traditional comadronas and facility-based health care providers over the course of their pregnancy, suggesting strong preference for a blended model of care among indigenous women in these regions. However, about 70% indicated that comadronas and public health personnel should work together to improve the quality of ANC services—and Maria shares their sentiment. “Some doctors or nurses do ask us as comadronas to help accompany their patients, but not all of them. Not all of them trust us or understand what we do,” she explains. “It would be nice if they would let us in with our patient when she is going to give birth, especially because not everyone [at the health facilities] can speak our language.” These views are also reflected in the responses of health workers surveyed; nearly 90% of the more than 900 MSPAS personnel interviewed identified a need to receive additional training to expand their culturally responsive care capacities.

Building on previous work in Guatemala, the Utz’ Na’n project has made significant strides since its launch in 2021 in mobilizing local partners to reduce barriers that indigenous women face seeking quality care during pregnancy. The project has also helped to increase recognition of the key role that comadronas play as providers of critical ANC services, especially in isolated rural areas. In collaboration with UVG, Utz’ Na’n is analyzing research results to generate recommendations for local policy advocacy with the MPSAS, as well as community-driven program strategies that respond to prioritized needs as identified through this research. This evidence-based approach aims to reflect local preferences and practices and continue to advocate for better engagement of comadronas as trusted providers within a blended model of care that meets the needs of indigenous communities in the Guatemalan Highlands.

*Maria is a pseudonym to protect confidentiality.