Nigeria: When a Doctor, and a Government, Respond

Nigeria: When a Doctor, and a Government, Respond

This excerpt was originally published on Global Health Now’s website.

In his newly released book, The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It, Jonathan D. Quick, MD analyzes local and global efforts to contain diseases like influenza, AIDS, SARS, and Ebola. Quick proposes a new set of actions, coined “The Power of Seven,” to end epidemics before they can begin.

In the following excerpt for Global Health NOW, Quick, a Harvard Medical School faculty member, senior fellow at Management Sciences for Health and chair of the Global Health Council, describes Nigeria’s response to Ebola, describing what it takes to stop an outbreak—and the consequences for humanity when we fail.

In July 2014, Patrick Sawyer, a Liberian-American lawyer who had been exposed to Ebola in Liberia, traveled to Nigeria for an important regional conference and collapsed in the Lagos airport. At the time, doctors at all the government hospitals were on a labor strike. The only hospitals that remained open were private ones like that in which Dr. Ameyo Adadevoh worked. The doctor who first saw Sawyer initially diagnosed him with malaria; Sawyer claimed he’d had no contact with anyone suffering from Ebola. But after seeing him on her rounds the next day, Dr. Adadevoh suspected Ebola. After a test for Ebola came back positive, she knew exactly what to do: she created an isolation area in her hospital to continue Sawyer’s treatment and to protect her staff.

Adadevoh’s battle to protect herself and others from infection wasn’t easy. The hospital wasn’t equipped with the proper protective gear, correct protocols for Ebola treatment, or a real isolation unit. Adding to the challenge, the Liberian government officials were pressuring the Nigerian government, insisting that the doctor discharge Sawyer so that he could attend the conference. But Adadevoh held her ground and refused to let him go. Four days later, Sawyer died of Ebola. Ten days later the doctor herself became ill and was taken to a poorly equipped, makeshift isolation ward, where she too died.

Had Adadevoh not stood up to the government, Ebola might have gripped Nigeria because of the doctors’ strike and the government’s lack of preparedness. But thanks to her courageous actions, Ebola in Nigeria was limited to just 19 cases and seven deaths, including hers. Nigeria was declared Ebola-free in October 2014, even as the epidemic raged on in West Africa. That’s an amazing feat in a country of more than 180 million people.

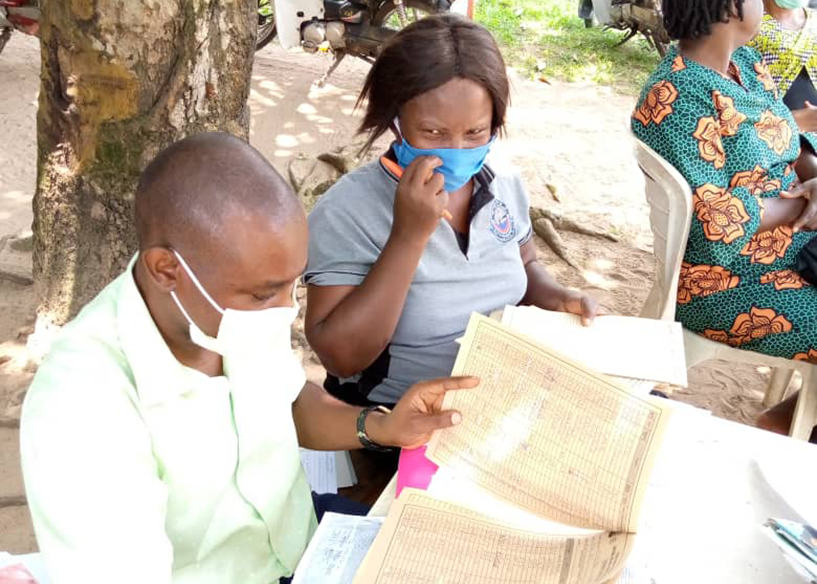

Prevention also involves locating everyone who has been exposed (“contact tracing”). As tragic as Dr. Adadevoh’s death was, it became a catalyst for Nigeria to mobilize against Ebola. And the country did a marvelous job of contact tracing. Nigeria was fortunate, because in 2012, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation had built an emergency command center to detect polio cases. The disease surveillance system at the center was now deployed to look for new Ebola cases. Nigeria mobilized a rapid-response team of 100 Nigerian doctors trained in epidemiology.

After Ebola struck, the government moved 40 of the Nigerian doctors to a central hub that coordinated Nigeria’s health ministry, WHO, UNICEF, the CDC, Médecins Sans Frontières, and the International Committee of the Red Cross. In what the WHO called “a piece of world-class epidemiological detective work,” the government ended up tracking 100 percent of all potential Ebola contacts in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city, where Sawyer landed, and 98 percent of contacts in Port Harcourt, where his nurse visited family. Nearly 1,800 health workers were rapidly trained and armed with protective gear. Safe wards were set up with enough beds and access to chlorinated water. In total, health workers made 18,500 face-to-face visits to check the temperatures of 900 possible contacts.

Nigeria wasn’t perfect in its response to Ebola. It took too long for the government to act, and the doctors’ strike slowed response too. Niniola Soleye, an employee of MSH and the niece of Dr. Adadevoh, wrote that her beloved aunt paid with her life because the Nigerian health system had been unprepared to deal with Ebola. “The system has since caught up, and Nigeria is today a model for other countries,” Niniola wrote. “But the loss of such a gifted doctor and family anchor is incalculable.” The story of her aunt was a vivid reminder to me that every death is personal, that we are all connected, and that there are terrible human consequences when health systems fail the people they are supposed to serve.

As the story of Ebola in Nigeria demonstrated, finding and treating the sick before the outbreak has a chance to spread is crucial. But Nigeria wasn’t the only country that prevented a local Ebola outbreak from becoming a national public-health emergency. In Senegal, “patient zero” was admitted to the hospital, having lied about his travel history. A week later, doctors found out that he had come from Guinea, and had him tested for Ebola. Senegalese officials closed the country’s borders and tracked 67 people who had been in contact with the patient, all of whom underwent voluntary quarantine and twice-daily monitoring by Red Cross workers. None ended up contracting Ebola; even patient zero survived.

These nations clearly showed that a good early detection–early response system—backed by enough trained health workers, equipment, facilities, and a public education campaign—can stop even the most infectious disease.

From THE END OF EPIDEMICS: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It by Jonathan D. Quick. Copyright © 2018 by Jonathan D. Quick, MC, and Management Sciences of Health, Inc. and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.