Kenya’s Primary Health Care Networks Can Help Deliver Better Care for All

Kenya’s Primary Health Care Networks Can Help Deliver Better Care for All

By Dr. Agatha Olago, Colin Gilmartin, Dr. Salim Hussein, and Dr. Elizabeth Wangia

On a recent morning in Isiolo County, Kenya, two nurses working at a rural health dispensary saw just a handful of patients. Yet several kilometers away, a sub-county hospital—intended for treating the most severe and complicated cases—faced a flood of patients traveling from nearby towns, the majority of whom were waiting for basic outpatient services like treatment for malaria and upper respiratory infections.

This phenomenon is not unique—patients frequently bypass lower-level health facilities and community health workers closer to their homes to seek services elsewhere, often at higher-level facilities perceived to be of better quality. Lower-level facilities often lack adequate staffing and frequently experience stock-outs of lifesaving medicines. Such mismatches of supply and demand contribute to widespread inefficiencies within health systems while patients delay seeking the care they need and incur higher costs, such as travel and out-of-pocket expenses. Unless governments find ways to address these inefficiencies, much-needed investments in primary health care (PHC) may fail to reach their full potential and slow progress toward achieving universal health coverage (UHC).

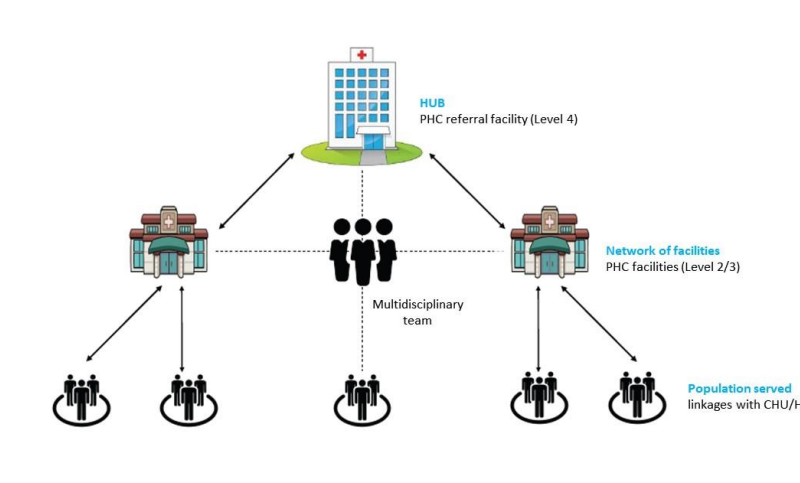

Many countries have started establishing networks of PHC providers. These primary health care networks (PCNs) efficiently deliver PHC services, reduce fragmentation, and provide advanced care when needed. As integrated teams, PCNs are responsible for delivering services to a defined population while ensuring the continuity of care through their referral and counter-referral systems. These networks promote access to basic services closer to home, refer complicated cases to higher-level facilities, share information for addressing performance issues, and identify suspected disease outbreaks. PCNs also share resources—they can quickly address stock-outs through a pooled supply of commodities and shift available human resources to where extra support is needed.

Recognizing these benefits, Kenya introduced the PCN approach in 2021. Taking the form of a “hub and spoke,” each PCN consists of a sub-county hospital serving as the hub to several health centers, dispensaries, and community health units that serve as the entry point to the health system and are responsible for reaching the most remote and disadvantaged populations (figure 1).

These PCNs have allowed for PHC to be delivered according to each county’s needs. The 18 counties implementing PCNs have reported enhanced integration of training, program implementation, supervision, and service delivery as well as greater teamwork among various cadres and improved monitoring and evaluation. Based on this initial success, the Kenyan government has called on all counties to set up PCNs.

Despite these early successes, Kenya lacks much of the necessary routine and high-quality data to assess and improve the performance of its PHC system while facing a considerable funding shortfall to respond to local population needs.

In anticipation of challenges like these, in 2020 Management Sciences for Health (MSH) and the Kenya Ministry of Health partnered to generate data on PHC facilities in six counties, assessing key indicators on their performance, levels of expenditures, and resource needs using MSH’s PHC-CAP Tool.

The analysis found that investment in the PHC system varied greatly across counties. To achieve universal access to PHC services, Kenya would need to invest additional resources compared to its current level of funding. This financial gap could also potentially be closed through the PCN approach, which aims to improve PHC efficiency, notably by leveraging existing human resources, improving the staffing mix among facilities, increasing demand for services, and instituting better referral practices to prevent bypass.

As other countries consider new models of PHC to promote better and more efficient service delivery, Kenya’s experience highlights several key recommendations and takeaways:

- Explicitly specify the services to which the population is entitled as part of a PHC benefits package and at which level of the health system each service is available. Align the package of services with a country’s available resources, accounting for the health system’s existing infrastructure, human resources, and governance.

- Ensure that a wide range of quality services are available at lower-level facilities. Many health centers and dispensaries in Kenya lack adequate equipment and medical supplies, while staff lack training and motivation to provide high-quality services, leading patients to self-refer to higher-level facilities. Investment in PHC facilities should not be limited to “brick and mortar” and should enhance the skillset and incentives of human resources and ensure adequate medical supplies and equipment.

- Institutionalize strategies for referrals and gatekeeping to optimize available resources. To reduce bypass and ensure that each level of the health system meets patient demand, some health systems have instituted specific referral policies and gatekeeping mechanisms. For example, patients can only access higher levels of care through referrals or by paying additional fees for direct access. In Kenya, the National Health Insurance Fund could potentially limit reimbursement for certain services if provided at hospitals while leveraging provider payment mechanisms to incentivize service provision at specific levels of the PHC system.

- Expand task-shifting of services to make more efficient use of the existing health workforce. To enhance the reach and impact of lower-level health facilities and workforce cadres, certain PHC services could be shifted away from higher volume facilities. For example, through Kenya’s Community Health Strategy (2020–25), paid community health promoters (a cadre whose value has not been fully realized and accepted) would deliver a greater proportion of preventive, educative, and promotive health services.

- Strengthen health information systems to routinely capture adequate data for enhanced decision making and performance monitoring. To help optimally channel resources for PHC, a combination of routine data is needed (e.g., number of types of health facilities, cadres of human resources, health service statistics, detailed expenditures). Together, these data can help to estimate the resource gap needed to deliver quality PHC services and identify where additional resources are needed or where there are opportunities to shift resources elsewhere.

- Ensure that all stakeholders are engaged and supportive of the approach. This includes, but is not limited to, faith-based organizations, the private sector, and key segments of the community such as women, youth, and persons living with disabilities.

As Kenya and other low- and middle-income countries seek to achieve UHC, they will need to mobilize additional financial resources for PHC. Spending better by focusing on some of the lessons from Kenya will help fully harness the benefits of a high-functioning PHC system.

About the authors

Dr. Agatha Olago is a Consultant Physician at the Ministry of Health in Kenya.

Colin Gilmartin is a Principal Technical Advisor for Health Economics and Financing at MSH.

Dr. Salim Hussein is the Head of Primary Health Care for the Directorate of Preventive and Promotive Health at the Ministry of Health in Kenya.

Dr. Elizabeth Wangia is the Director of Healthcare Financing for the State Department for Medical Services in Kenya.