Peru: Communities Collect Data to Bring Change Home

Peru: Communities Collect Data to Bring Change Home

This article was originally published on the USAID website.

At sunrise in the Valle de los Ríos Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro (VRAEM) region of Peru, community members visit their neighbors’ homes to collect data on childcare practices, women’s health practices, as well as more sensitive topics regarding psychological or physical violence against women and children. These early morning in-home visits are designed to accommodate families’ farm work schedules and ensure a safe space for open conversation. Management Sciences for Health–Peru (MSH–Peru), a USAID partner, leads this research-intervention activity that seeks to better understand the relationship between social capital and health, gender disparities, and protection of women, children, and adolescents against violence in families. Core to their approach is community-led action, informed and motivated by community-owned data.

The VRAEM region, which has the highest levels of poverty, continues to bear the remnants of the armed conflict in the 1980s and 1990s. The region also suffers from gaps in service delivery, reflected in the persistence of childhood malnutrition and anemia, as well as continuing illicit production of coca. This is the context in which MSH–Peru has facilitated the formation of 17 community neighborhood boards, which are on a path of driving their own change.

MSH–Peru’s engagement with the community neighborhood boards begins with its “Moral Leadership and Community Management Program,” a series of five workshops in which board members talk through what it means to be a leader, conduct community mapping, develop a “tree of dreams,” and review community issues and goals. Following these workshops, the MSH–Peru team provides ongoing technical assistance to each neighborhood board to help operationalize these concepts through developing management tools, including a community diagnostic, an action plan, and a health, nutrition and violence prevention survey tool. All of these products are then presented to and discussed with the rest of the community by the board.

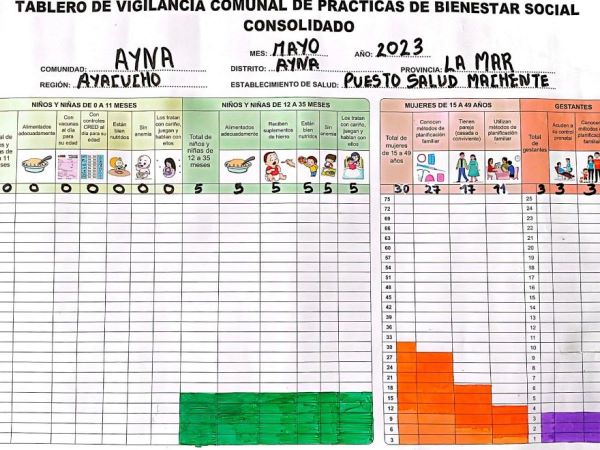

MSH–Peru works with the community neighborhood boards to adopt a survey tool that helps monitor household practices, which helps the board gain an understanding of health, sanitation, nutrition, domestic violence, and other social welfare practices in their community. The survey includes questions such as:

- “Are children under six months exclusively breastfed?”

- “From 12-35 months, does your child receive 3-5 solid or semi-solid foods during the day?”

- “Is your child up to date on vaccinations for his or her age?”

- “Does your child have their growth health checks up to date?”

- “Is the child well nourished?”

- “Does the child have anemia?”

- “Does the family treat the child with affection? Do they play and talk with them?”

- “Do you know family planning methods?”

In the district of Ayna, the board visited and surveyed 38 families within the community.

With assistance from MSH–Peru, the neighborhood boards graph and analyze data together with community authorities. This helps identify the most frequent problems in each community, and provides the board with information to use in decision-making and action planning with the participation of community residents.

While the activity is still in its early stages, MSH–Peru plans to support neighborhood boards to reconvene with community members every three months to share data, discuss short and medium term goals informed by the data, and incorporate these into their action plans (see image below). The plan includes problems identified by the community, actions the community will take to resolve each, the person responsible for leading the action, the associated costs, and the end goal. The action plan undergoes several rounds of revisions, with assistance and advisory services provided by the MSH–Peru team.

For example, in Ayna, the community survey identified the presence of malnutrition in school-aged children as a priority issue. To improve this, the board worked with the local health authorities to coordinate appointments so that children could receive a medical evaluation and receive free counseling and treatment. The community neighborhood board proposed holding demonstration sessions on food preparation for children under 3 years old and pregnant women, and the MSH Peru team coordinated with health personnel to carry out these sessions. The board will continue to monitor families with malnourished children through conducting the survey every six months.

“Information is important for making decisions!” Edgar Medina, MSH–Peru Executive Director, shares. The information collected through the community diagnostic and the survey help communities recognize their own problems and take action, which is essential for change to occur.

“This is what all the work to provide information and raise awareness about social problems is about. It helps communities recognize their own problems in health, sanitation, and other areas which they may have previously recognized as normal and unproblematic,” said Miriam Santivañez, the Monitoring and Evaluation Manager at MSH–Peru.

The collection and analysis of information has been useful for the community neighborhood councils to see that the problems affect the entire community and not just individuals. According to Medina, “[This community-led approach]…is breaking the paradigm that the external consultants are the ones who have to make the community diagnosis. The community can generate its own information and make its own decisions with that information!” For example, part of the data collection includes information on people with disabilities. While typically an underrepresented topic, “data helps to show the problem exists,” Medina adds.

Engaging local governments is also part of MSH–Peru’s approach, as this is crucial to longer-term sustainability of change. Peru’s National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA), and other government entities also provide services in communities like Ayna, and MSH Peru seeks to complement this support rather than duplicating or replacing it. Medina says, “The information [data and analysis] is also shared with the municipal authorities so it can be considered in the formation of district development plans and included in budgets, prioritizing local input in the allocation of public resources.” The data is a foundation upon which communities, health workers, and local government officials can collectively take action to improve health and sanitation practices and reduce domestic violence.

Medina notes that the process is not without its challenges. Weekly meetings for the neighborhood boards are a big time commitment, and some groups have opted to meet in two separate groups to accommodate varying schedules. MSH–Peru enables this flexibility as the boards find structures that work for them. Some of the neighborhood board members, especially women, primarily speak Quechua, and it is hard for them to communicate in Spanish in the group. MSH uses interactive methods to overcome this gap, including ensuring other group members can translate.

Medina also emphasizes that this is not a quick process. He encourages, “This is a process of accompaniment. Some communities learn how to use the tool quickly, and others need more time.” MSH–Peru initially planned only one technical assistance session for each community to prepare them for community management and surveillance, but found that while this worked for some neighborhood boards, additional sessions were needed for most communities. As a local partner, MSH–Peru is committed to providing the level of support communities need, seeking their empowerment for community self-management.